From Solitude to Solidarity

A crude reimagining of community, wrestling with making something new, and acknowledging the enclosure we’re all in.

If you haven’t read the first part of this mini essay, be sure to read this first:

After a season of retreat, after pulling back from the noise of social media, performance culture, and the grind of constant engagement, the creative individual (you) might feel more grounded. There is something necessary about that withdrawal. Turning down the volume of online life can reawaken that quiet sense of purpose which so often gets buried beneath the ever-changing algorithms and metrics. But once the stillness settles in? Another feeling begins to rise; the ache for something more than just clarity: The need for belonging.

We live in a time that promises connection at every turn. Comments, likes, shares, and validating DMs seem to suggest that we are part of a community. But too often these gestures stop short of actual intimacy. This doesn’t imply sexual intimacy, but rather, raw communication. Vulnerability. Transparency. Opening up about your ‘real life’, still standing on the cusp of true honest connection. Art traded to be ‘Meaning’, using tools of capitalistic monetization. A Portfolio, that duals as a cathartic outlet. It is within this that we are surrounded by activity but not always by care. While the messages or the comments can feel good, do we acknowledge that it’s possible to share our work constantly and still feel deeply alone? This is the paradox of a creative life in the digital age. There is always someone watching, but rarely someone caring.

Creative platforms reward consistency, output, and visibility. It’s how they are designed and function, and in doing so, chemically reward our dopamine and destroy our well-being. We perform. We present. The artist becomes a brand. The brand becomes a habit. And the habit becomes a cage. Even if we break free, even when we step away from the spectacle and reclaim a more honest voice, we are still left with a question. Who are we creating for?

Online creative culture encourages us to be visible, but it rarely helps us feel seen. Maybe the answer lies in doing more of what we are naturally prone to: Looking at what existed before the feeding of the beast. Especially when it comes to commodifying our work and skill.

Excerpt from Art for Brand’s Sake? Factors that influence artists’ acceptance of a brand collaboration (Bomnüter, Matovina, & Hansen, 2022)

Brand managers and advertising agencies seem to be well aware of this influence, as they turn to the arts for their representational power (Schroeder, 2010). Research indicates that artworks may positively impact the perception and evaluation of products, which has been theorized as “art infusion effect” (Hagtvedt & Patrick, 2008) or, in the case of collaborating with famous artists, “icon myth transfer effect” (Scarpaci et al., 2018). 1

Looking Back to Look Forward

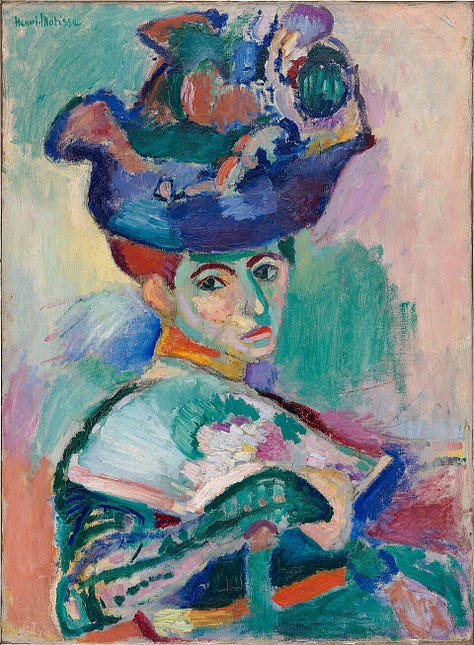

Before timelines and notifications, or the monetization of our individual and group aesthetics (not to mention the pressure to remain relevant), artists gathered together in physical spaces that valued conversation over content. These were the salons, studios, cafés, and schools where art was made, shared and questioned.

Book Recommendation: A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

In 1920s Paris, Gertrude Stein opened her home to writers, painters, and thinkers. I’ve written about this before, but you see, they gathered to be challenged far more than to be agreed with or understood. Hemingway, Picasso, Joyce, Laurencin, Picabia, and countless others did not come just to network. These were spaces where ideas clashed, styles were debated, and creative boundaries were pushed. Those rooms, filled with disagreement and brilliance, even in varying creative fields, gave birth and evolution to movements and styles we still pull from to this day. The Dada2 spirit, for example, continued to evolve into broader avant garde expressions. Even the fragmented sentence, once radical in literary Modernism, still echoes in how we write today.

What these older models of community offered was not perfection. They offered presence. They created conditions where creativity could unfold honestly. They remind us that artistic identity is not something we build alone. It is something we shape through relationship; the one thing that truly lacks nowadays.

Building the New Commons

I first learned about Commons or common grounds, through reading Graham Greene novels. Most of his characters have their finest intimate and internal epiphanies while walking through the fields of Clapham Common. The beauty of writing like this is that Greene isolates a character in the one place where they are visible for all to see. So I like to think of ‘Commons’ as Vulnerability.

A moment of reflection. Commons were lands legally owned by landlords or lords of the manor, but where common people held traditional rights to use certain resources. They could graze their livestock, collect firewood, or gather materials. Now think about our common area online. The place I say is vulnerable. Is it not odd that the social media corporations (the landlords) have given us this vulnerable playground, yet continue to find ways to commodify it and trick us into feeling safe? Is this common area, meant to be free for expression, actually just a fenced-off enclosure?

If we believe this space to be one of vulnerability, and if solitude truly was the first step in uncovering our creative selves, then solidarity must be that second step. The challenge now is to rebuild these communities that prioritize our presence, together.

Features like Instagram’s broadcast channels, designed and promoted to highlight direct connection, often feels like a one way megaphone. Artists toggle between shouting into the void and acting as their own marketing departments. This collision of personal expression and brand management only highlights how difficult it is to feel present, or true, when the platform still expects performance.

What, then, is the alternative to broadcasting what is essentially your soul?

A shared table. Going for walks with your partner. A group chat specifically meant for sharing your fears and doubts without judgement before coming together in person to discuss. If art is the documentation of existing, then our vulnerability doesn’t need to be polished and edited. It just needs to be real. I remember a friend of mine saying to me once, ‘Trust is born in small rooms.’

In this new ‘commons’, that we control, feedback matters more than likes. Questions matter more than applause and the pressure to have or be a finished product is replaced by the permission to be in the process. These are the places where creativity can deepen and become sustainable.

What We Must Do

To build these spaces, we must resist the habits that digital life encourages. We must unlearn the urgency of content cycles and remember the pace of conversation. We must stop measuring our worth in visibility and begin to trade efficiency for depth.

As I write this, I don’t write it as my profession which I am well aware is laid in the duality of art and business. I write this as the musician and writer and photographer I am. The one that writes poetry in his spare time for no one but his journal.

As the year unfolds, let’s try to resist the pull to reenter the noise too quickly. As war and chaos spins around us, let us try and move slowly towards each other instead. Build new rooms, new tables, and new traditions that support not just our work, but our well-being. This is not a rejection of ambition. It’s a simple redefinition of success. Success might not be a large following. It might just be a simple friendship. It might be a space where you are allowed to make something strange and true without needing it to perform well.

The creative life will always contain struggle. But it should not be marked by isolation. We do not have to do this alone. Not now. Not anymore.

A question I’ll leave you with. If I say that the ‘creative community’ today is often algorithmically assembled, not spiritually aligned, what is the first thing that comes to mind to make you either agree or disagree. If your job is heavily built on the marketing of your art, are you an artist or just a marketing wiz? Do you know which one you are?

Do you know who you are?

Bomnüter, L., Matovina, A., & Hansen, R. (2022). Art for brand’s sake? Factors that influence artists’ acceptance of a brand collaboration. HEC Montréal, Carmelle and Rémi Marcoux Chair in Arts Management. Retrieved from https://gestiondesarts.hec.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/22029_Paper.pdf

Schjeldahl, P. (2006). Young at Heart. The New Yorker, The Magazine, June 26, 2006. Archived at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/06/26/young-at-heart-2